A Reading List for America's Birthday. Books, films, speeches, interviews on how we got here, and where else we can go.

From James Fallows's BREAKING THE NEWS Jul 03, 2025 on substack

The 31-year-old Bill Moyers, as White House Press Secretary for Lyndon Johnson in 1965. Moyers, who became one of the country’s most influential and respected broadcasters, died last week, at 91. (Corbis via Getty Images.)

As a pre-holiday special, this post is an old-style grab-bag listicle, with items I’ve been “meaning” to write about further. Who knows when that will happen. But for now, some reading and viewing tips:

1) A China book: ‘Breakneck’

I’ve started reading another book about China that seems worth attention. “Another,” because last month I recommended Patrick McGee’s excellent new Apple in China, which is a gripping reportorial narrative and which, I predict, will change the way you look at any piece of Apple equipment from now on. Or the way you read any story about tariffs, “decoupling,” and US-Chinese economic dealings overall.

These good China-themed books keep coming. The most recent one I’ve seen is by the tech analyst Dan Wang and is called Breakneck. Its subtitle might make you think it’s just another in the tedious “who is number one?” series. That subtitle is China’s Quest to Engineer the Future. I can say that, 150 pages in, it’s far subtler and more interesting than that.

Breakneck got my attention in its very first paragraph, which in fact is all one sentence.1 It reads as follows:

Every time I see a headline announcing that officials from the United States and China are once more butting heads, I feel that the state of affairs is more than just tragic; it is comical too, because I am sure that no two peoples are more alike than Americans and Chinese.

As they would put it in a rom-com: You had me at “no two peoples are more alike.” That’s a main message Deb and I took from our years of living in China, and to me it’s a crucial “tell” about whether someone is worth listening to on the subject.

These are similar people, separated by different systems,2 each dealing with the plusses and minuses of their respective national approach. These plusses and minuses are Wang’s main theme—the differences between the “lawyer” system in the US, and the “engineer” system in China.

Another “tell” for me about books: After reading the first few chapters, do I feel like going on? This far into Breakneck, I want to read the whole thing. Check it out.

2) A film: ‘Facing Tyranny.’

Last week PBS aired an 83-minute film about Hannah Arendt, in its American Masters series. It’s called Hannah Arendt: Facing Tyranny, and it is very much worth seeing in our times.

Hannah Arendt died nearly 50 years ago, when the news about US governance revolved around Vietnam, Watergate, and the Nixon resignation. So she had nothing specific to say about the collapse of governance in the Doge/MAGA age. The last news coverage she might have read about Donald Trump was how Roy Cohn guided Trump and his father through racial-discrimination complaints filed by Richard Nixon’s Department of Justice.

But the film is full of reminders of why Arendt’s first famous book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, which came out in the 1960s, is such a relevant guide to the politics of our immediate moment. And why “totalitarian” is indeed the right term to describe the MAGA era.

Just two samples. First, about the kind of people attracted to serve a totalitarian cult leader:

Totalitarianism in power invariably replaces all first-rate talents, regardless of their sympathies, with those crackpots and fools whose lack of intelligence and creativity is still the best guarantee of their loyalty.

Look at the roster of Trump appointees, and weep.

And, about “truth” and “lies”:

One of the greatest advantages of the totalitarian elites of the twenties and thirties was to turn any statement of fact into a question of motive.

She was talking about the “twenties and thirties” of the 1900s, but we see this every day in our own “twenties.” Trump in his disordered Q-and-As, the histrionic Karoline Leavitt in her “press briefings,” the likes of Kristi Noem and Pete Hegseth—they all meet any question of fact with an attack on motive. “You’re from the fake media, so you would say that…”

It’s worth seeing the film for the many unsettling Arendt resonances.

2a) A lighter film.

The Netflix eight-part series The Residence is set in a (fictional) White House, and has a totally different vibe. Funny, smart, wry, suspenseful. Like a highly sophisticated version of Clue. You may feel worse after watching any news. You’ll feel better after watching this.

3) A loss: Bill Moyers.

Bill Moyers died last week, at 91. He was a phenomenally productive and principled journalist and explainer. He was also a very complicated man: A seminarian who became a precocious White House press secretary. A newspaper publisher who became a broadcast icon. He was personally closer to LBJ than most other still-living people whom Robert Caro might have interviewed for his epic book series. But Moyers famously declined ever to discuss LBJ with Caro.

I had close dealings with Moyers in the 1970s, when I was in my 20s and he, at age 40, was undergoing his metamorphosis from political practitioner to revered journalist and public voice. I highly recommend Eric Alterman’s piece about the Moyers of those years, which in turn cites a long Q-and-A he did with Moyers back in 1991. He says this about Moyers’s reluctance to talk with Caro:

He did not feel right about trying to justify himself to Caro. It felt too egotistical to him, he said….

My own theory, however, was that he was deeply, and I mean deeply, pained by some of the things he went along with as a young man in the Johnson administration, though these are not the ones he has sometimes been accused of. He was, he explained when I questioned him in some detail on some of the allegations in the 1991 interview, “I was a very flawed young man, with more energy than wisdom.”

Based on my more limited involvement with Moyers, this rings true. You’ll see more details in Alterman’s pieces. (With a caveat I mention below.3)

Here’s a relevant point about Moyers now. Through his career he appeared frequently on Fresh Air, with Terry Gross. One of his last interviews there was in 2017, near the start of Trump’s first term, when Kellyanne Conway was still his press secretary. By comparison with her successors, Conway seems almost like Diogenes. But Moyers told Terry Gross then that the level of facile lying from Trump and his representatives was new and unknown in American life:

MOYERS: Look, I was not a perfect press secretary. I made a lot of mistakes. But I did feel that the job was to try to help the reporters get what they needed to tell their stories and help the president understand what the reporters were trying to do. I never did think of myself as a propagandist for the administration or the White House.

But these people I'm listening to and have been watching in the Trump administration are really just, you know, they're lying. They're deceiving us.

And if you don't call that out, then the lie becomes a part of the lived experience of the people who are watching or listening.

Part of our lived experience. This takes us right back to Hannah Arendt. The Trump team lies about everything, so as to make people think that nothing can be true. Last year’s movie The Apprentice dramatized Roy Cohn teaching Donald Trump exactly how this process worked. The press has become inured to it. Trump’s delusions and flat-earth lies, and those of people who speak on behalf, are no longer “news,” because they’re no longer new. But they matter. For reasons Arendt and Moyers, in their different ways, explained.

No one (to my knowledge) has done a full biography of Billy Don Moyers and his many lives. I’ll read that one when it comes out.

4) ‘A government as good as its people.’

At a summertime gathering in Plains, Georgia, in 1976, Billy Carter with a shirt prefiguring the political culture wars of our times. (Owen Franken/Corbis, via Getty Images.)

Fifty years ago, during his still-unmatched run from obscurity to the White House, Jimmy Carter liked to say that America needed “a government as good as its people.”

Carter had a sardonic edge, and he fully recognized the catty way that line could be read. (“Yeah, our government is as good as our people—that’s the problem!”) But he could project his belief in its earnest, positive side, with its hope for redemption. And I think the way he explained it, just before election day in 1976, is worth attention in our current predicament.

This statement by Carter came at an evening fund raiser in New York, late in October. I was there, as part of Carter’s traveling team. But out of fatigue and distraction I barely registered what he was saying, in the kind of unscripted riff that always showed him at his best. I could, though, tell that the well-heeled crowd was listening closely.

Carter leapt right in: “People like us don't suffer nearly as much as the ones to whom I talked in Harlem this afternoon,” he said:

And in Winston-Salem this afternoon. And in Miami this morning, on the beach. And last night in Tampa. [This gives you an idea of the campaign-trail travel schedule.] They come [to rallies], having suffered when the unemployment rolls increase, because their families stand in line looking for a job. And they come having suffered when the unemployment rate rises, because they have to cut into their own personal expenses—food, clothing, housing.

Most of us, don't.

In our times, he could have been talking about the people about to lose their rural hospitals, their coverage for nursing homes, their life saving but expensive medicines, because of the Medicaid cuts the GOP Congress is bloodlessly preparing to inflict.

Carter then said that most of these people—most Americans he’d met during his life in Georgia, and in his campaign travels through the preceding years—were thinking not just about their own troubled circumstances but also about the idea of doing positive things together, with their neighbors and fellow citizens. “I think of the Civilian Conservation Corps that I knew about when I was a child on the farm,” Carter said to the crowd in Manhattan:

I think about the REA when it turned on the electric lights in my house when I was fourteen years old. [This was FDR’s Rural Electrification Administration, which transformed life in rural America. Throughout the South, Carter always got a cheer on this line, from families who could remember life before light bulbs.] I think about the Marshall Plan under Truman, and aid to Turkey and Greece, and the United Nations, and the formation of the nation of Israel. I think about the Peace Corps in which my mother served when she was about 70 years old.

Every politician looks backwards to cite ideals and examples of American greatness. The emphasis in Carter’s presentation was his insistence that the public hungered for something better, again:

We don't have those concepts any more, of sacrifice and a struggle upward, and inspiration and pride.

We as a nation have been disillusioned, we've suffered too much, and in too short a time, the assassination of great political leaders—John Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr. A tragic war, hidden deceitfully from the American people in the case of Cambodia, a national scandal, the resignation and disgrace of a President of the United States, and the Vice President of the United States.

Reminder: This was a time when the Republican party would tell a Republican president that it was time for him to step down. A time in which the term “disgrace” had some meaning.

“All of these things and others made millions of American people lose faith and trust in our own government,” Carter said.

To all these people I say every day, many times: Please. Don't give up. Don't be apathetic. Give our system another chance….

If we can only have leaders once again who have vision, and who are as good in office as the people who put them in office. That's what this campaign is all about….

Government by the people—it's as simple as that.

What’s the relevance now? Civic life is an endless see-saw between the strengths, weaknesses, character, and desires of the public, and the quirks, rules, and rigidities of the system through which people’s desires are expressed. That’s what every non-totalitarian form of government is set up to handle.

Right now, we’re at a moment where the system is failing, more grievously than the people as a whole are:

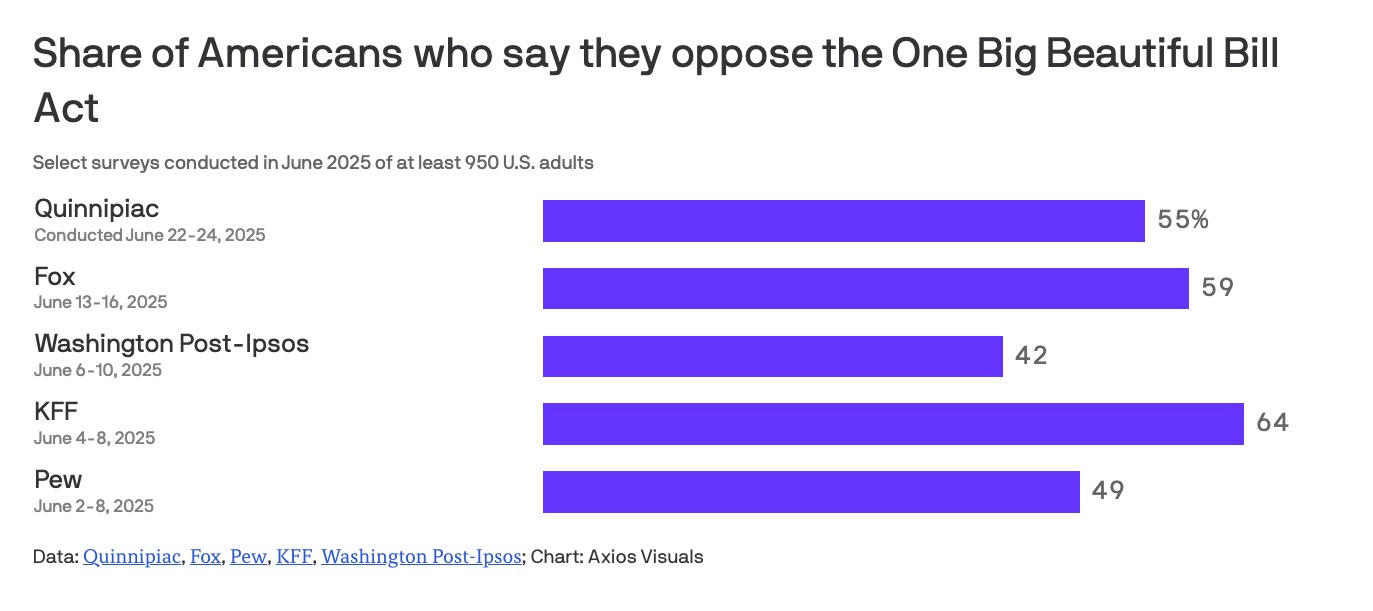

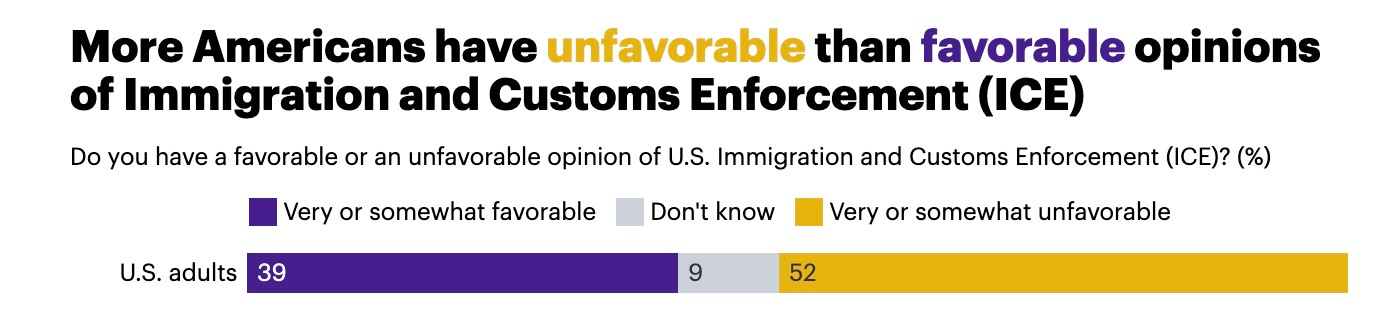

Evidence suggests that most people do not want tax cuts mainly for the richest one-tenth of 1%. They do not want a multi-trillion dollar increase in the national debt. They do not want Medicaid and Medicare to be reduced, and rural hospitals closed. They do not want school, libraries, science, and FEMA to be cut, so that those already rich can be richer still. They want “violent criminals” to be deported, but not mass roundups on their streets.

When given the chance this past year, strong majorities have voted against the momentum of MAGA and Doge. We’ve seen this in Wisconsin, in Virginia and New Jersey, most recently in New York City. We’ve seen this in ever-larger demonstrations. We see it in almost every poll:

The machinery of democracy is supposed ultimately to connect what people want, with what the system delivers. Of course the linkage is imprecise, and time-delays are built in, and there are swings from one extreme to another.

But we are at an extreme. Lisa Murkowski told us last month that “we are all afraid,” speaking for her fellow Republicans. This week she showed us how afraid, with her last-minute cave-in to Trump. Last night, breathless live news reports told us about the House Republicans “holding out” against Trump. This morning, they too have caved, as everyone knew they would.4

Look at that Jimmy Carter impromptu speech again. He wound up:

I haven't given up hope for our country.

I believe in America.

Once the people rule again, we can solve our economic problems. Once the people rule again, we can have a fair tax system.

Once the people rule again, we can reorganize the government and make it work with competence and compassion because the American people are competent, and we're compassionate.

Once the people rule again, we can have a foreign policy to make us proud and not ashamed.

It all depends on the people and how accurately we represent them, who have been selected by them as leaders.

It’s a long way, from that hope, to majorities in the Senate and House, and lifetime seats on the Supreme Court5. But you have to have a sense of where you want to go. That’s what I sensed in last week’s election in New York, and the preceding weeks’ protests around the country, and most off-year elections we’ve had so far. Our institutions have again failed us: Much of the press, nearly all of the legislative GOP, at least six members of an autocratic Supreme Court. It’s up to the rest of us, again.

Happy Independence Day!