CMOS: New Questions and Answers

Our style guide of choice, The Chicago Manual of Style, has added new questions and answers to their Q&A section. Read this and other related articles at www.chicagomanualofstyle.org

It’s the time of the month when The CMOS posts their new questions and answers. Read below to find answers to your style questions or even questions you didn’t even thought you had!

New Questions and Answers

Q. Dear CMOS! I have a grammar question that has thrown our small department into a tizzy. In a sentence like “There are an even number of kittens on the veranda,” we are evenly split (pun intended!) as to whether “There are” is correct since there are a plural number of kittens or “There is” is correct because the number is (see? “is”) even. We’ve checked Garner’s entry for “number of,” which seems to throw down in favor of “there are,” but those of us in the “there is” contingent aren’t convinced. Any light the CMOS team can shed on this?

A. The expression “a number of” is an idiomatic phrase that means “some” or “several,” which is why a plural verb would normally be expected after “a number of kittens” used by itself: A number of kittens [or Some kittens] are on the veranda—or, if you invert the sentence, There are a number of kittens [or some kittens] on the veranda.

But if you change a to the, the idiom goes away, and the focus switches to the word number itself, making a singular verb the correct choice: The number of kittens on the veranda is huge. If you then invert that, however, you’re back to the plural: A huge number of kittens are on the veranda. So far, we’re mostly in line with Garner’s Modern English Usage, 5th ed. (2022), under “number of.”

But huge in that inverted example keeps things idiomatically plural: A huge number of kittens simply means lots of kittens, an expression that requires a plural verb. An even number, by contrast, means just what it says: a number that’s even instead of odd. And though it isn’t one of the examples featured in Garner, an even number doesn’t seem to have an obvious plural idiomatic equivalent like some or lots that could replace it; therefore, a singular verb is arguably the better choice: There is an even number of kittens on the veranda.

In other words, the number of kittens on the veranda is even (🐈🐈🐈🐈) rather than odd (🐈🐈🐈), an observation that puts the number ahead of the kittens. Nothing is certain when it comes to kittens, but that’s our take.

Q. In CMOS 16.71, why is Leonardo da Vinci indexed under “L”? And in an article that refers to people by surnames on subsequent mention, should he be referred to as “Leonardo” or “da Vinci”?

A. You can ignore Dan Brown and others who’ve rebranded the archetypal Renaissance man as “Da Vinci.” The name is Leonardo, and he came from Vinci (da Vinci), an Italian town in the region of Tuscany.

Leonardo can be referred to in full as Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (as noted on page 69 of Walter Isaacson’s 2017 biography, Leonardo da Vinci [Simon & Schuster])—in which “di ser Piero” means he’s the son of a man named Piero (ser is an old social title that was similar to “sir”). Leonardo’s father was also da Vinci, which isn’t a surname but rather an epithet (see CMOS 8.34). Leonardo and Piero are given names (i.e., first names).

Because he lacks a surname, Leonardo da Vinci is properly indexed under “L” and would be referred to in the text as Leonardo—that is, after having been introduced as Leonardo da Vinci.

Q. When is it proper to use an ampersand? Thank you.

A. In edited prose, use of the ampersand—&*—is normally limited to

terms like R&D and Q&A that are always spelled with an ampersand (see also CMOS 10.10);

corporate names like AT&T and Simon & Schuster that reflect the usage of a particular company or brand (see also CMOS 10.24); and

ampersands in verbatim quotations.

An ampersand may also be used when mentioning the title of a work that includes one (subject to editorial discretion; see CMOS 8.165). And if you’re working with HTML, you may need an ampersand in a character reference like (for a nonbreaking space)—or & (for an ampersand).

__________

* According to the OED (and other sources), the ampersand evolved from a stylized rendering of the Latin conjunction et (and) in the form of a ligature, and the word ampersand is an English-language corruption of “& (and) per se and” (“and by itself [is] and”)—a phrase that differentiated the symbol from &c., an old-fashioned way of writing et cetera (and others).

Q. Hello, I use old-style figures in the text of my document. Do you have any recommendations for whether they should then be used also for footnote markers in the body text and/or the footer?

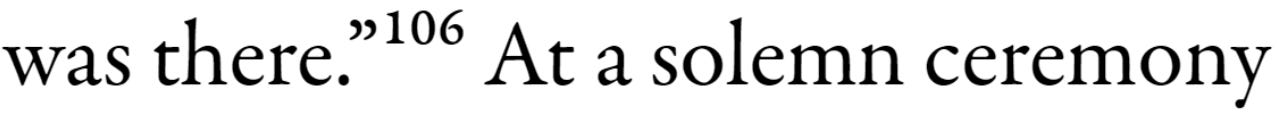

A. Our designers prefer lining figures for the superscript note reference numbers in the text, even in works that otherwise feature old-style figures—as in the book Eleanor of Aquitaine, as It Was Said: Truth and Tales about the Medieval Queen, by Karen Sullivan (University of Chicago Press, 2023). The corresponding numbers at the beginning of each note, however—which in Chicago style aren’t superscripts—would use old-style figures.

Superscript lining figures in the text:

Old-style figures on the baseline in the corresponding note:

Notice how the digits in the superscript 106 are all roughly the same height, ensuring that a note number 1, for example, will be about the same size as a note number 6. This matters more with the smaller superscripts than it does for the numbers that sit on the baseline—even in the text of the notes, which is slightly smaller than the main text. (The Sullivan book features endnotes, but the advice would be the same for footnotes. See also CMOS 14.24.)

Q. Have we abandoned altogether the rule to put note reference numbers (and only one per sentence, please) at the end of the sentence? I’ve prepared indexes for a number of academic monographs lately where note reference numbers are sprinkled willy-nilly throughout the text.

A. CMOS does still say that a note reference number1 is best placed at the end of a sentence or clause,2 but there isn’t any limitation—technical or otherwise3—that might prevent authors from placing such a reference4 elsewhere, or that might bar authors from using more than one in a sentence.5

So if a publisher or editor has failed to enforce the spirit of CMOS6 relative to note reference numbers—and the book’s already at the indexing stage7—there’s not much we can do to help you.8

__________

1. Or symbol—*, †, ‡, etc.

3. A note reference number can literally appear anywhere in a document.

4. Like this one.

5. This sentence has five.

6. See note 2 above.

7. As described in CMOS 16.108.

8. Other than show with this answer how distracting such notes can be. :-)

Q. In a collection of (some previously published) essays all by one writer, does one cite the author as the editor too? CMOS 14.104 and 14.106 seem to come close, but they don’t address this exact situation. In the source I’m working with, the title page does not credit the author as editor, but some of the essays were previously published. Thanks!

A. No, you wouldn’t cite the author as both author and editor of the book. For example, “The Girl in the Window” and Other True Tales (University of Chicago Press, 2023) is an anthology of stories written by Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Lane DeGregory that were originally published in the Tampa Bay Times (formerly the St. Petersburg Times).

The title page credits DeGregory as author of the book and Beth Macy as author of a foreword. No other contributor is listed. So even though it was DeGregory herself who compiled, edited, and annotated the stories, you wouldn’t cite her as editor also.

Besides, the words “edited by” don’t have the power to tell the reader that some or all of the essays in a book were previously published. If that info is relevant, you can say so either in the text (as we’ve done near the beginning of this answer) or in a note. But for the citation itself, follow the title page.

Q. We have to number our paragraphs in the research paper we are writing. What is the proper way to do this?

A. CMOS doesn’t cover this, but a convenient way to number paragraphs in MS Word or Google Docs is by using the feature for numbered lists.

In either program, you can start by selecting the paragraphs you want to number. Then use the numbering icon, which in Word is in the Paragraph group under the Home tab; in Docs, there’s a similar icon in the toolbar above the document.

You can then use the ruler in either Word or Docs to move the paragraph numbers into the left margin and to format the paragraphs with first-line indents (which may require setting a tab stop). See also CMOS 2.12.

In Word, adding a custom paragraph style will enable you to reapply this same formatting wherever it’s needed. In Docs, you’ll need a third-party add-on to do the same. But both programs include a format painter that can be used in a similar way, allowing you to copy the automatic numbering and other formatting from one paragraph and apply it to others as needed.

Word and Docs both allow you to stop and restart numbering as needed to skip over headings and the like. And if your document includes numbered lists in addition to the numbered paragraphs, you can use the options in either program to create multiple independently numbered lists.

If you need even more flexibility, and you’re comfortable digging a little deeper into the software, you can try using Word’s Seq field code to insert sequential numbers that are independent of the numbered list feature and can be placed anywhere in your document. For more details, see the article “Numbering with Sequence Fields,” by Word guru Allen Wyatt, at Tips.net.

October Q&A

Q. It is my contention as a longtime editor and writer (and avid amateur cook and baker) that the apostrophe in “confectioner’s sugar” should precede the “s” in “confectioners.” Yet in recipes throughout the US, for many years the apostrophe has typically followed the “s” of “confectioners.” I maintain that this is incorrect and a fairly recent (in decades) development. What do you think?

A. We agree that the spelling confectioner’s sugar makes sense—by analogy with, for example, baker’s yeast. With that placement of the apostrophe, the term refers to a type of sugar used by a confectioner (singular). But we have to side with common usage here. Not only is the spelling confectioners’ sugar more common than the alternatives (including confectioners sugar, where the plural noun is used attributively), it’s a lot more common.* The dictionary at Merriam-Webster.com doesn’t even list an alternative (as of October 2023). Neither does The American Heritage Dictionary.

So maybe just accept that the term confectioners’ sugar (with the apostrophe following the s) refers to a variety of sugar used by or typical of confectioners (plural) considered as a category or group as opposed to a type of sugar used by an individual confectioner, a relatively arbitrary distinction. Anyone who expects apostrophes to be consistent across similar terms may not be happy, but the farmers at the farmers or farmers’ or farmer’s market will probably understand.†

__________

* By way of comparison, baker’s yeast is the accepted spelling today, but that spelling was neck and neck with bakers’ yeast in published books until about 1950, after which it became the norm (or, you could say, rose to the top).

† Chicago prefers farmers’ market (see CMOS 7.27).

Q. Hello, I’m wondering how to style the name of a television program that has been assimilated into the cultural lexicon so that references to it are not truly references to the show. In particular, an author said, “When I landed at the airport, it was as if I had entered the Twilight Zone.” (He makes many references to this.) I feel it should be capitalized but not italicized, but I can’t find anything to say one way or another. Can you help? Thanks!

A. In your example, you’re right—the reference isn’t to the television show; rather, it’s to the fictional realm made famous by the show. So we agree with your treatment. Had your example been worded instead as follows, italics (and a capital T for The) would have been correct: “When I landed at the airport, it was as if I had arrived on the set of The Twilight Zone.”

Q. Does CMOS have a rule for using one el or two in verbs ending in “ing”? For example, “traveling” or “travelling”? “exceling” or “excelling”?

A. If you’re an American traveler who’s traveling in the United States, use one l; if you’re a British traveller travelling in the UK, use two. But if you plan on excelling in either region, you’ll want to use two l’s for that word.

That’s because of two competing conventions: (1) When -ing or -ed (or -er) is added to a word of two or more syllables that ends in a consonant preceded by a single vowel (like travel and excel), the consonant is usually doubled if the stress falls on the final syllable. Accordingly, you’d write traveling and traveled (because the stress in travel is on the first syllable) but excelling and excelled (the stress in excel is on the second). But (2) travelling and travelled (and traveller) are exceptions to the rule in British but not American usage.

We don’t know the reason for that exception, but we can offer as evidence this footnote from page 16 of the eighteenth edition of Horace Hart’s Rules for Compositors and Readers at the University Press, Oxford (published in 1904, the first year Hart’s guide was offered to the public):

We must, however, still except the words ending in -el, as levelled, -er, -ing; travelled, -er, -ing; and also worshipped, -er, -ing.—J. A. H. M.

That footnoted exception applies to the rule about not doubling consonants when the last syllable isn’t stressed. “J. A. H. M.” is James Murray, the main editor of the original Oxford English Dictionary, who is also credited on the title page of that edition (and others) of Hart’s Rules as one of two people responsible for revising its “English spellings.”

The three exceptions noted in the footnote above are still followed in British English. In American English, by contrast, level and (as we have seen) travel do not double the l, but worship usually doubles the p (as in British English).

CMOS used to include a list of preferred spellings—as on pages 37 and 38 of the first edition (published 1906), which showed traveler with one l and (in a decision backed by logic that nonetheless didn’t stick) worshiper with one p. CMOS now defers to Merriam-Webster for such decisions.

Q. I can’t get a definite answer on how to punctuate a sentence that starts with “trust me.” For example, “Trust me, you don’t want to do that.” Would this be considered a comma splice? Would it be better to use a period or em dash, or is the comma okay? What about “believe me” or “I swear”?

A. Any phrase like “trust me” at the beginning of a sentence that is roughly equivalent to a “yes” or a “no” can normally be followed by a comma (as covered in CMOS 6.34):

No, you don’t want to do that.

is like

Trust me, you don’t want to do that.

whereas

Yes, I’ve edited the whole document.

is like

Believe me, I’ve edited the whole document.

and

I swear, I’ve edited the whole document.

You could use a stronger mark of punctuation for extra emphasis:

I swear! It’s not a comma splice!

or

I swear—it’s not a comma splice.

among other possibilities

But a simple comma will be the best choice in most contexts (and won’t get you in trouble for using a comma splice—at least not with us).

Q. Dear CMOS, As regards a foreign word that needs to remain in its original language in a lengthy comparative analysis, would you inflect this word so as to reflect its grammatical position in a sentence consistent with its inflection in the original language? The word at issue is Pflichtteilsberechtigter (roughly, a forced heir). In its original German, the singular of the word could be either Pflichtteilsberechtigte or Pflichtteilsberechtigter, depending on whether it is preceded, respectively, by a definite or an indefinite article. As a plural, it could be either Pflichtteilsberechtigten or Pflichtteilsberechtigte, depending on whether it is preceded, respectively, by a definite article or a zero article.

Consistent with German grammar, the word would be spelled/inflected as follows in these four sample sentences (the first two being singular usages and the second two plural usages): “A Pflichtteilsberechtigter enjoys special rights in German succession law. The Pflichtteilsberechtigte, the son of the deceased, sued the testamentary heir for a portion of the estate. Courts require Pflichtteilsberechtigte to submit certain forms. In the case at issue, the court required the Pflichtteilsberechtigten to first appear before a notary.”

Employing spellings consistent with German grammatical rules on inflection could potentially confuse readers unfamiliar with these rules (or leave them thinking the writer/editor has been careless!). But adopting a wholesale simplification (e.g., writing Pflichtteilsberechtigter whenever it is a singular usage and Pflichtteilsberechtigte whenever it is a plural usage and not further inflecting according to German grammar) could confuse—or at least annoy—those readers who will have an appreciation of German, which will likely be significant in this case. We look forward to any input you have to offer!

A. Extrapolating from CMOS 11.3, it’s usually best to inflect a non-English word that hasn’t been anglicized just as it would be in the original language, as when referring to more than one Blume (flower) as Blumen (flowers).

Accordingly, the examples in your second paragraph seem good to us, with one possible caveat. Out of context, it may not be obvious to all readers that “the Pflichtteilsberechtigten” in your last sentence is supposed to be plural. If necessary, you could rephrase—for example, as “each Pflichtteilsberechtigte,” where the German noun is now clearly singular (and inflected as it would be following the)—or whatever best conveys the intended meaning.

But you should consider explaining for your readers how these inflections work—for example, in a note the first time one of these terms appears in your text. The explanation near the beginning of your question (“In its original German, . . .”) could easily form the basis of such a note.

Q. Our style guide states that “healthcare” must be treated as one word, but would this extend to varieties, such as mental healthcare? Merriam-Webster lists “mental health” as a separate noun, so I’m genuinely confused whether it should be “mental health care” or “mental healthcare.” Thank you!!

A. Good question! The version “mental health care,” which keeps the term “mental health” intact, makes a little more sense than “mental healthcare.” A hyphen might make that pairing even clearer—“mental-health care.” But because the term “health care” belongs together just as much as “mental health” does, the unhyphenated phrasing is still better.

In your case, however, since “healthcare” is in your style guide as one word, we’d recommend going with “mental healthcare” to jibe with your use of the word “healthcare” in other contexts. Readers are more likely to be put off by an obvious inconsistency than by a slight asymmetry.

Q. Hello! Here’s a fun citation style question: How do you cite website content that’s accessible only through the Wayback Machine from Archive.org?

A. Cite the content as you normally would, but credit the Wayback Machine and include the URL for the archived page. For example, let’s say you were to mention the fact that Merriam-Webster.com still listed the hyphenated form e-mail in its entry for that term as late as January 2, 2021, with email offered as an equal variant (“or email”). You could cite your evidence in a footnote as follows (see also CMOS 14.233):

1. Merriam-Webster, s.v. “e-mail,” archived January 2, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, https://web.archive.org/web/20210102004146/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/e-mail.

Notice the URL, an unwieldy double-decker consisting of two consecutive URLs stitched together. If you wanted a shorter URL, you could cite only the second part (i.e., the original URL for the content), as follows:

1. Merriam-Webster, s.v. “e-mail,” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/e-mail, archived January 2, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

That’s a bit more concise than the first example, but readers will need to enter the original URL at the Wayback Machine (which they’ll have to find on their own) and then use the date to get to the right version of the page.

Either approach is acceptable as long as you’re consistent.