U.S. Army overturns convictions of 110 Black soldiers in 1917 Houston riot at Camp Logan

Now Memorial Park. Congratulations to Angela Holder and all who aided in this restoration of justice.

More than a century has passed since 110 Black soldiers stationed at Camp Logan were convicted of mutiny, murder and assault in the 1917 Houston Riot, with 19 of them executed at Fort Sam Houston. Now those convictions have been overturned.

Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army Michael Mahoney has directed the Army Review Boards Agency to "set aside" the convictions of all soldiers from the 3rd Battalion, U.S. 24th Infantry Regiment. The Army will recognize the overturned convictions in a ceremony Monday at the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum in Midtown. Their service records will now reflect that they served honorably.

"It can't bring them back, but it gives them peace," said Angela Holder, whose great-uncle, Cpl. Jesse Moore, was one of the executed soldiers. "Their souls are at peace."

The decision, reached weeks ago by Army Secretary Christine Wormuth, restores each of the soldiers' individual rights, privileges and properties lost — their descendants may now be eligible for benefits. An Honorable Discharge Certificate "as a testimonial for honest and faithful service" has been issued for each soldier.

The reversal is unlike any other in the Army's history.

“This is not only the largest murder trial in American history, this is also the largest court-martial in American history, and no case this large or this serious with this many death penalties has ever been completely overturned by the Army on review,” said historian John Haymond, who along with South Texas College of Law former professor and retired military officer Dru Brenner-Beck co-authored the petition that Wormuth based her decision on. Their work on the case was pro bono.

“In legal terms, you would say this case is sui generis, meaning that it stands alone. It is truly unique,” he added. "This is the Army recognizing it's never too late to do the right thing and correcting its error of the past."

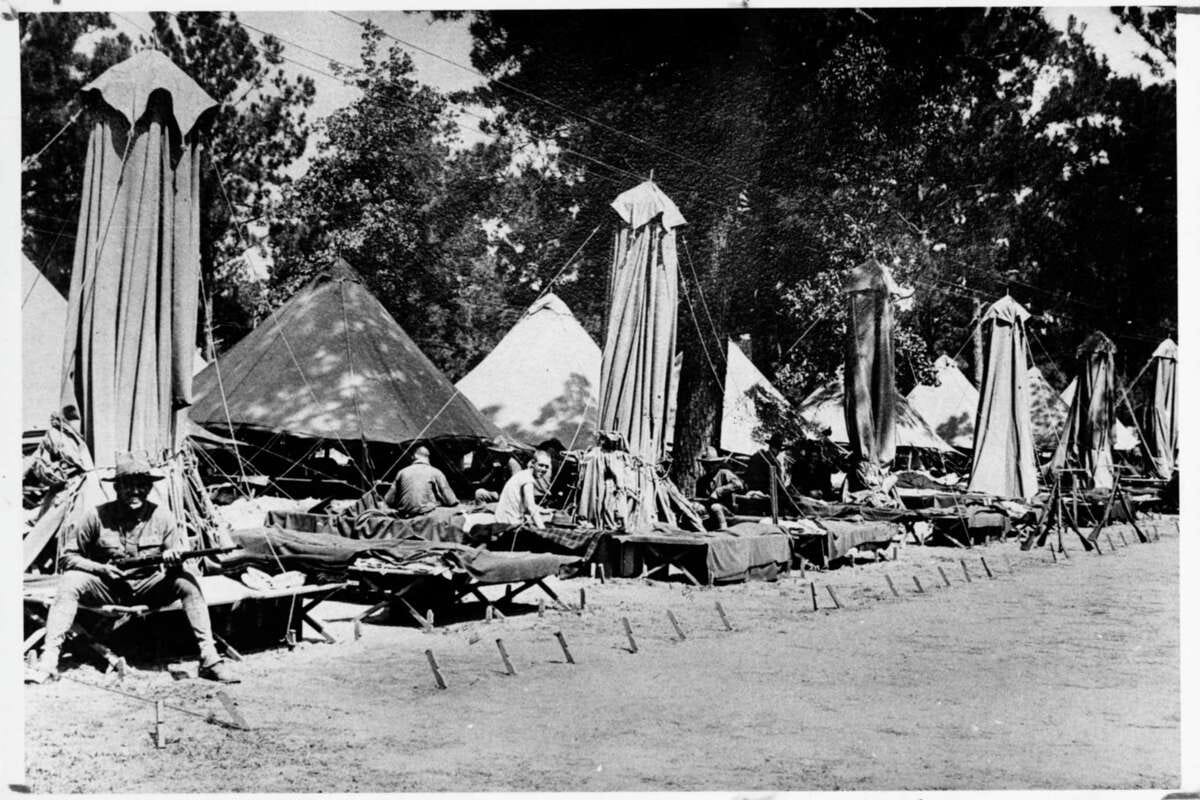

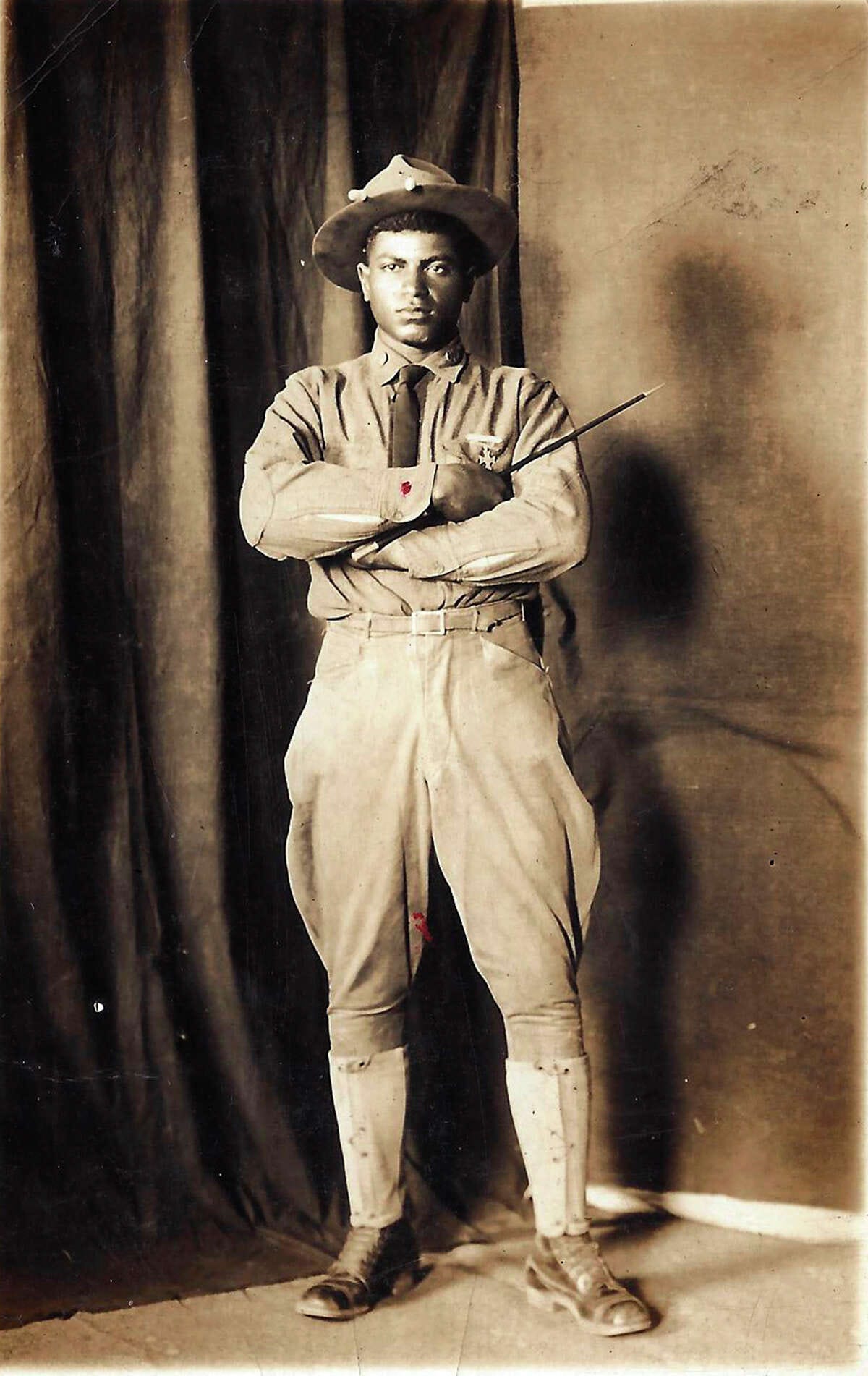

Members of the all-Black 24th Infantry Regiment, often referred to as Buffalo Soldiers, arrived on July 27, 1917, and were ordered to guard the construction of Camp Logan, a 7-acre training base that is now part of Memorial Park, after the U.S. declared war on Germany during World War I.

Three African American soldiers pose against a fence at Camp Logan.

Soldiers marching from Camp Logan to a tabernacle on Vida Street, now Waugh Drive.

GIs' tent city - World War I soldiers at Camp Logan. (Houston Chronicle Files)

The city they encountered was a hostile one. Houston strongly enforced the Jim Crow segregation laws of the South.

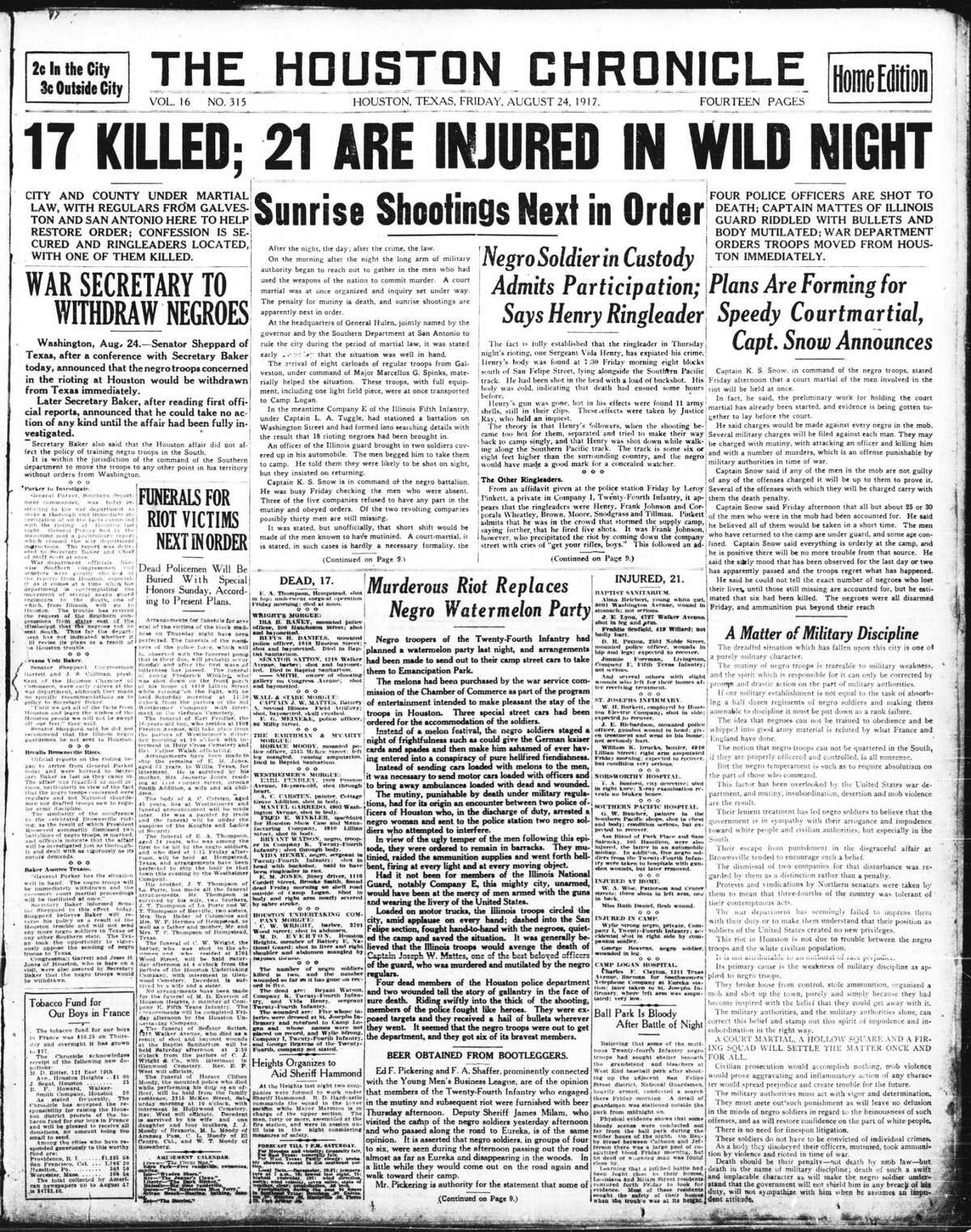

On the night of Aug. 23, 1917, Camp Logan soldiers clashed with whites. Seventeen people, including five police officers, would end up dead that night — most of them white.

The violence had roots in Houston’s racial strife. The regiment was staying near the construction site in the Washington Avenue area. Disputes at the site included insults involving white workers, police and soldiers; sometimes the encounters were violent, according to transcripts from the trial, preserved at South Texas College of Law. The soldiers were often met with racial slurs. Police were known to arrest and beat soldiers who stood up to them when words were exchanged.

The match was lit on the morning of Aug. 23, when police officers Lee Sparks and R.H. Daniels raided a craps game led by young Black men. Police assaulted a Black woman; a soldier was arrested when he protested. A few hours later, a military police officer, Cpl. Charles Baltimore of Company I, talked with officers Sparks and Daniels about the arrest.

The conversation ended with Sparks pistol-whipping the corporal, who ran, was shot at three times, and was later arrested and beaten again. Rumor got back to the camp that Baltimore was dead, sparking talk of revenge among the soldiers. He later returned alive, though bloodied. That night a shot rang out and someone cried, “The mob is coming!” prompting soldiers to rush for their rifles and set up a defensive perimeter around the 24th’s camp.

The white battalion commander abandoned his post, leaving other officers to try to control the panicking troops. At that point, Sgt. Vida Henry ordered soldiers in Company I to march out of the camp in formation. Melee ensued.

Henry was later found dead. Pvt. Bryant Watson, Pvt. Wiley Strong and Pvt. George Bevens also were killed.

Houston was placed under martial law the following morning.

Jason Holt, a New Jersey lawyer and descendant of Pfc. Thomas C. Hawkins, who was executed, likens sending Black soldiers into a southern town to waving a red flag. "The country was still in the throes of the Jim Crow era and not many years post-slavery," he said. "With T.C. Hawkins, there's conflicting testimony as to where he was and what happened during the course of the incident. I'm not suggesting that there was the appropriate amount of fairness with any of the soldiers."

One officer, Maj. Harry Grier, represented all the defendants throughout three courts-martial. Grier, who was not an attorney, was reportedly given 10 days to prepare. Haymond's research indicates that prosecutor Col. John Hull commended Grier for not raising issues of race during the trial. Grier also made public statements on day 2 of the trials that mutiny had been proven, contrary to his clients' best interests.

Holder and Holt bristle at the word "mutiny." They prefer the "incident."

In an excerpt from his summary of the historical and legal facts of the 1917 Houston Incident, Haymond explains why: "In the list of uniquely military crimes, mutiny holds a singular position… It is natural and entirely appropriate, then, that when military personnel today first encounter the history of the Houston Mutiny of 1917, their most common immediate reaction is to condemn the men who were accused of that crime."

His belief is the Army prosecution failed to prove that 63 soldiers participated in mutiny within the required standard of military law. Within 12 hours of Maj. Gen. John Ruckman's sentencing in 1917, 13 condemned men were hanged. By September 1918, six additional soldiers were executed.

"If you have the largest courts-martial in the history of the United States, and you have one person representing 63 people who isn't even a lawyer, any semblance of a fair trial kind of goes out the window," Holt said. "Some were incarcerated, a few others were executed subsequently, but the first 13 did not have an opportunity to raise issues that could have mitigated the severity."

On the morning of his execution, Hawkins wrote a final letter to his parents in North Carolina: "Dear Mother & Father, when this letter reaches you I will be beyond the veil of sorrow. I will be in heaven with the angels… I am sentenced to be hanged for the trouble that happened in Houston, Texas, although I am not guilty of the crime that I am accused of."

Why did the Army's action take more than 100 years?

"That's a fair question," Haymond said. "So many of the records were classified for the longest time and not cleared for release until the 1970s. Military law is so different from civilian law."

Holder submitted the original petition, a posthumous pardon request, through the Department of Justice in 2017, but that document only addressed the first 13 men who were executed. Much of her case was based on a presentation between Fred Borch, one of the few people publicly discussing Camp Logan at the time, and then-South Texas College of Law Houston professor Geoffrey Corn.

Corn took an interest in Holder. Within two years, he brought key players into the fold, including fellow former intelligence officer Brenner-Beck. In 2019, they presented their findings to regional NAACP representatives.

"We had two principal objectives — explain that they'd done it wrong, you have to go through the Secretary of the Army, and that the NAACP should endorse a resolution at the national level," Corn said. "We were way too under-inclusive. Every one of those soldiers suffered an injustice, and the Army deserves to give them remedy for that."

Approval was unanimous. The NAACP supplied funding, and South Texas College of Law designated Brenner-Beck an adjunct professor under the Actual Innocence Clinic, where dozens of students worked on a petition for clemency over a two-year period.

"We had students working on the project who were themselves veterans. They had a nuanced understanding of command structure, mutiny and the Army's responsibility for what may have occurred," says South Texas College of Law vice president, associate dean and clinical professor Cathy Burnett. "When they read the transcripts and saw what happened, their views changed."

Brenner-Beck and Haymond's petition for clemency landed on Mahoney's desk of the Army Review Boards in January 2022. Three groups studied and reviewed files requested from the national records agency on the 110 convicted soldiers.

Mahoney never felt pressure to predetermine any outcome, he said. He was tasked to investigate and provide a recommendation, which is what the Army Review Boards did, following a process used for tens of thousands of cases prior.

"In the end, I recommended to the Secretary of the Army in May 2022 that the convictions be set aside and are now honorable discharges," he said. "There's no physical evidence. And eyewitness accounts, with 1917's level of outdoor electrical lighting, produced inconsistent testimony. One, single defense attorney had to represent all 110 officers. We would not do that today obviously. None of the white officers were charged or convicted. None of the white citizens were charged or convicted of anything."

Setting aside the convictions acknowledges they were never guilty, he said.

Holder cried when she got the call that the decision had been made.

As a young girl, she had vowed to find her great-uncle. In 2001, she finally visited the graves of Moore and his comrades at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio. A marker stands where 17 of the regiment's soldiers are buried.

"I remember going to each tombstone and saying, 'I'm going to do something,'" she said. "The wheels of justice turn. They turn slowly, but they do turn. With this decision, the promise has been kept. It's been a lifelong mission for me."

Holder and Holt will attend the ceremony Monday where the Deputy Secretary of the Army and Under Secretary of the Army will discuss the 1917 Houston Incident and corrective action. The Army also will launch a website directing people to the National Records Agency to potentially identify more descendants, Mahoney said.

"One hundred and six years ago, when this happened, I would dare say the men of the 124th Infantry would not have thought this would be possible," Holt said. "It's a tremendous loss. At the same time, we're gratified and grateful the clemency petition has been successful and the convictions have been set aside."