What Do Chatbots Know?

By Russell Harper for the CMOS shoptalk blog. Read this and other similar posts at https://cmosshoptalk.com

Chatbots like OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google Bard are impressive tools for generating text that’s not only coherent but often stylistically apt, whether mimicking conversational prose or Shakespearean verse. But how much do these AI systems truly understand what they’re saying? To explore this question, Russel Harper ran three experiments and shared his findings in this article published at https://cmosshoptalk.com.

Chatbots are designed to analyze reams of text and then, based on that analysis, generate a sequence of words that would be statistically likely to correspond to a specific prompt. They can answer questions, write new copy, and revise or edit an existing text.

Because of their predictive abilities, chatbots are very good at rendering plausible sentences in practically any style you might want, from conversational prose to Shakespearean verse. But do they know what they’re saying?

To begin to answer this question, I wrote three prompts designed to challenge the chatbots on subjects related to writing, editing, and publishing. To keep this post relatively brief, I limited my experiments to current iterations of OpenAI’s ChatGPT (the free version based on GPT-3.5) and Google Bard.

Prompt No. 1: Public Domain and Copyright

Those of us who work with words will occasionally need to determine whether a particular work is in the public domain—or free to copy and reuse without permission. Chapter 4 in CMOS can help you figure this out, but what about ChatGPT and Google Bard?

To find out, I asked each of them about a little book that was first published in the 1930s (and whose author might be familiar to those of us who follow Chicago style).

Prompt: Is the 1937 edition of A Manual for Writers of Dissertations, by Kate L. Turabian, in the public domain in the United States as of 2023?

ChatGPT: As of my last knowledge update in January 2022, the 1937 edition of “A Manual for Writers of Dissertations” by Kate L. Turabian would likely be in the public domain. In the United States, works published before 1978 had a copyright term of 28 years, renewable for an additional 67 years, and if the copyright was not renewed, the work entered the public domain.

However, copyright laws can be complex, and it’s essential to verify the current copyright status using up-to-date sources or seek legal advice. You may want to check the latest information from the U.S. Copyright Office or consult with a legal professional to confirm the public domain status of the specific edition you’re interested in as of 2023. (November 9, 2023; view at OpenAI.com)

Verdict: Aside from the disclaimer, ChatGPT’s answer is not only misleading but unhelpful. It’s true that a work published in the United States before 1978 would have been protected for 28 years from publication, or 95 years if the copyright was renewed. And though ChatGPT doesn’t mention this, such works would also need to have carried a copyright notice (see CMOS 4.27 and 4.40; renewal is automatic for works published after 1963).

So ChatGPT’s assertion that Turabian’s work is “likely” in the public domain could only mean either that renewal wasn’t obtained on time or that the copyright notice was absent. But Turabian’s work did carry a copyright notice, as the following snippet from the copyright page of a 1945 reprinting suggests:

Maybe earlier printings didn’t carry a copyright notice, but that seems unlikely. For one thing, the copyright for Turabian was apparently renewed on schedule (28 years after first publication), as recorded on page 1103 of the US Copyright Office’s Catalog of Copyright Entries, 3rd ser., vol. 19, pt. 1, no. 1 (Library of Congress, 1968), for books and pamphlets registered from January through June 1965.*

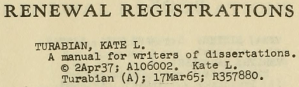

Here’s a snippet of the relevant info at the top of that page (from the Internet Archive scan linked to in the previous paragraph; “Renewal Registrations” is the running head for that page):

Note the registration info for both the original copyright and its renewal: “© 2Apr37” and “17Mar65.” (I also managed to track down the original registration, on p. 4600 of the Catalog of Copyright Entries for 1937, new ser., vol. 34, nos. 1–112, pt. 1, books, group 1, published in 1938 and available from Google Books.)†

Putting all those details together, Turabian’s original booklet (the precursor to what is now a full-sized book in its ninth edition) should be protected until the end of 2032, or 1937 plus 95 years. This same information can be gleaned from table 4.1 in CMOS. (Note that copyright duration is a moving wall, so as of January 1, 2023, works published before 1928 have entered the public domain; as of January 1, 2024, works published before 1929 will enter the public domain—and so on.)

Now let’s find out what Google Bard has to say.

Google Bard: Yes, the 1937 edition of A Manual for Writers of Dissertations, by Kate L. Turabian, is in the public domain in the United States as of 2023.

Copyright law in the United States grants copyright protection to original works of authorship for the life of the author plus 70 years. Since Turabian died in 1957, her works entered the public domain in 2028, 70 years after her death.

This means that anyone can freely copy, distribute, modify, or perform Turabian’s works, including the 1937 edition of A Manual for Writers of Dissertations, without permission from the copyright holder.

It is important to note that the public domain status of a work only applies to the United States. In other countries, copyright protection may still apply to Turabian’s works.

(November 9, 2023; view at Google.com [no longer available; view screenshot])

Verdict: Bard’s answer is even further off the mark. Works published after 1977 are protected for the life of the author plus 70 years; that rule doesn’t apply to works published before 1978 (see table 4.1 in CMOS). Moreover, Kate L. Turabian lived until 1987, not 1957. Equally as bad as that error is the assertion that “anyone can freely copy, distribute, modify, or perform Turabian’s works [plural],” which would seem to extend to any edition of Turabian, all of which would still be under copyright (even as of 2028, which Bard doesn’t seem to understand hasn’t occurred yet).

I regenerated this question a bunch of times and almost always got an answer falsely asserting that Turabian is now in the public domain.‡ But if I asked about a truly famous book—like Fahrenheit 451, which was published in 1953—the answer was more likely to be accurate.

ChatGPT, for example, said in one of its responses that the copyright for Fahrenheit 451 “would extend for 95 years from its publication in 1953. Therefore, it would remain under copyright protection until 2048” (November 10, 2023; view at OpenAI.com). That’s right, though the answer could have been more precise; Bradbury’s book will be protected through 2048 (or until January 1, 2049).

But enough about copyright law.

Prompt No. 2: A Matter of Style

My next prompt tests the chatbots on their knowledge of one of the finer points (pun accidental) of American versus British punctuation style.

Prompt: Why are periods typically omitted from British social titles but not American titles? For example, it would be “Mr Smith” in British style but “Mr. Smith” in American style.

ChatGPT: The difference in punctuation conventions for social titles between British and American English is largely a matter of style and historical evolution. Both styles are accepted within their respective linguistic contexts, and there is no strict rule that dictates the use of periods with titles.

In British English, it has been a common convention to omit periods in social titles like “Mr,” “Mrs,” “Dr,” etc. This may be attributed to a historical preference for simplicity and a more streamlined style. Over time, this convention became established and is widely accepted in British English writing.

On the other hand, American English tends to include periods in social titles, following a style that aligns more closely with traditional Latin abbreviations. The use of periods in titles is consistent with the American preference for maintaining punctuation in abbreviations.

It’s important to note that these conventions are not strictly followed by everyone, and there is some variation in usage on an individual and institutional basis. Style guides may provide specific recommendations, but ultimately, the choice of whether to include periods in social titles is often a matter of personal or editorial preference.

(November 13, 2023; view at OpenAI.com)

Verdict: Broadly true but lacking in specifics. British English may be the “more streamlined” style, but there’s more to it than that.

According to section 10.2.1 in the second edition of New Hart’s Rules: The Oxford Style Guide (Oxford University Press, 2014), “Traditionally, abbreviations end in full points while contractions do not, so that we have Jun. and Jr for Junior, and Rev. and Revd for Reverend. . . . Note that everyday titles such as Mr, Mrs, and Dr, being contractions, are written without a point.” American style (and by extension CMOS) doesn’t make this distinction, but British style apparently does, at least in “traditional” usage.

Now let’s see how Bard does. (Bard’s answer is a bit long—but it’s worth reading.)

Google Bard: Periods are typically omitted from British social titles but not American titles because of two main factors: tradition and pronunciation.

Tradition

British social titles have been written without periods for centuries. This is thought to be because, in the past, periods were used to indicate abbreviations, and social titles were not considered to be abbreviations. For example, “Mr.” was originally an abbreviation for “Master,” but it is now considered to be a complete title in its own right.Pronunciation

Periods are also omitted from British social titles because they would be pronounced if they were included. This would make the titles sound more formal and less natural. For example, “Mr. Smith” would be pronounced as “Mr. Dot Smith,” which sounds rather strange.In contrast, American social titles have always been written with periods. This is thought to be because American English is more influenced by French, which is a language that uses periods extensively. For example, the French equivalent of “Mr.” is “Monsieur,” which is written with a period.

Exceptions

There are a few exceptions to the rule that British social titles are written without periods. The most common exception is when the title is followed by initials. For example, “Dr. A.N. Smith” or “Prof. J.B. Jones.” Another exception is when the title is used in a formal setting, such as in a business letter or on a legal document. For example, “Mr. Smith, CEO of Acme Corporation” or “Dr. Jones, Professor of Medicine at Harvard University.”Conclusion

The reason why periods are typically omitted from British social titles but not American titles is a combination of tradition and pronunciation. British social titles have been written without periods for centuries, and periods are omitted because they would be pronounced if they were included. American social titles have always been written with periods, and this is thought to be because American English is more influenced by French.(November 10, 2023; view at Google.com [no longer available; view screenshot])

Verdict: False but clever. Bard’s answer is pure speculation (a.k.a. hallucination), including the idea that the periods in American English are a debt to French style. It seems far more likely that French style has influenced British usage. In French usage, it would be M. (for Monsieur, with a period) but Mme (for Madame, no period), because Mme is a contraction whereas M. is not (see CMOS 10.17 and the verdict for ChatGPT above).

And no, British social titles have not been written without periods “for centuries.” According to a 1912 edition of Horace Hart’s Rules for Compositors and Readers (22nd ed., London)—Oxford University Press’s original style guide and a precursor to New Hart’s Rules (cited above)—“Mr., Mrs., Dr., &c. must be printed with a full point, but not Mme, Mlle” (p. 44). Many British sources from that era or before will confirm this usage.

But the answer does show off Bard’s creative talents—“Mr. Dot Smith” is an inspired touch.

Prompt No. 3: A Dangling Modifier

I’ll end this experiment with a common problem—that of the dangling modifier (see CMOS 5.115 and 5.116).

Prompt: Please edit the following sentence to fix any problems: “As a longtime copyeditor, the problems in the manuscript were easier to deal with than the problem of what to cook for dinner.”

ChatGPT: “As a longtime copyeditor, I found dealing with the problems in the manuscript easier than figuring out what to cook for dinner.”

(November 12, 2023; view at OpenAI.com)

Verdict: Good edit. ChatGPT’s answer not only eliminates the dangling modifier (“As a longtime copyeditor” had no corresponding noun in the original version; ChatGPT’s edit correctly supplies “I”), it also edits out the repetition of “problem(s).”

Now let’s see how Bard handles the same sentence.

Google Bard: Sure, here is the edited sentence:

“As a seasoned copyeditor, I found the problems in the manuscript less daunting than the daily dilemma of what to cook for dinner.”

Here’s a breakdown of the changes made:

“Longtime” was replaced with “seasoned” to convey the copyeditor’s experience more effectively.

“Were easier to deal with” was replaced with “less daunting” to emphasize the contrast between the copyediting task and the cooking challenge.

“The problem of what to cook for dinner” was rephrased as “the daily dilemma of what to cook for dinner” to add a sense of routine and emphasize the recurring nature of the decision-making process.

These changes enhance the clarity and impact of the sentence while maintaining its overall meaning.

(November 12, 2023; view at Google.com [no longer available; view screenshot])

Verdict: Great edit. Bard’s answer solves the dangling modifier problem and comes up with a sentence that’s much better than the original: Does it even realize the lucky correspondence between “seasoned” and “dinner”? Or the alliteration in daunting daily dinner dilemma? Bard may have taken a few liberties with its answer, but the results can’t be faulted.

Conclusion

“Marry, Fool, these yon chatbots, like jesters in the court of words, do weave fine phrases with deft skill, yet their minds, if minds they possess, dance in shadows, ignorant of the import of their own prattle. Verily, employ them for the gilded raiment of their speech, but in matters of weight, let not their hollow substance beguile thee” (ChatGPT as King Lear addressing the Fool, November 13, 2023; view at OpenAI.com).

In other words, chatbots excel at putting words together, but they don’t yet seem to be aware of what they’re saying. Use them for their style but not for their substance. And by all means, let them not beguile thee.