XIX Corps Breaks through the Siegfried Line

An article by The National World War II Museum of New Orleans. Read this and other similar articles at www.nationalww2museum.org.

In a lesser-known operation that presaged the horrors of the deadly Battle of Hürtgen Forest, the XIX Corps broke through the Siegfried Line north of Aachen, Germany, in October 1944.

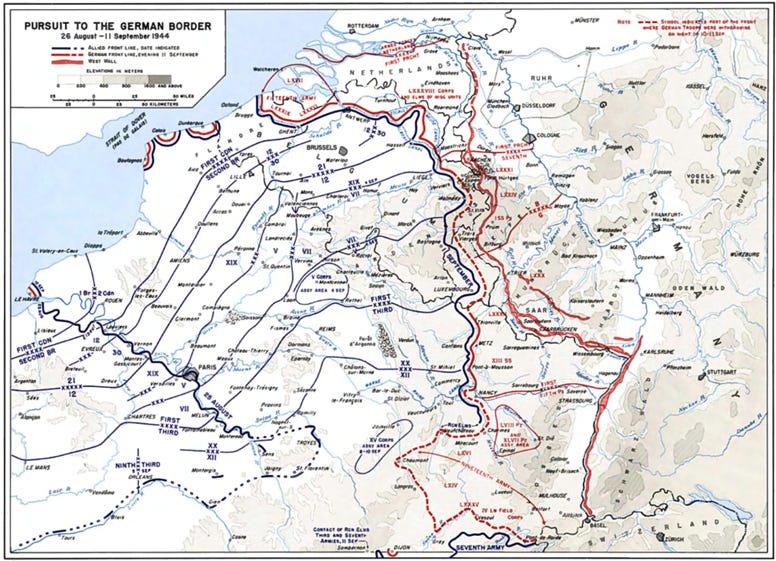

After the Allied breakout during Operation Cobra in late July 1944, the previously static situation in Normandy exploded into a rapid pursuit of the routed German troops. With Paris liberated and Brittany secured, the Allies looked to the east, beyond the Roer and Rhine Rivers to the German frontier. Optimistic that the war could end before the new year, General Dwight Eisenhower ordered offensive operations all along the front line, which stretched from the English Channel to the Mediterranean Sea.

The Allies soon found that the logistic infrastructure could not sustain the speed of their advance. Planners expected before D-Day that the beachhead would expand gradually to the east as the troops fought their way off the beaches and through France. The complex hedgerow terrain frustrated these plans, however, limiting the Allied advance to yards per day. When the breakout finally took place at Saint-Lô on July 25, the front moved so rapidly that logisticians could not repair rail lines, roads, or pipelines quickly enough to keep pace. The lack of a functioning port along the Atlantic coast only made the situation worse.

Pursuit to the German border. US Army Center of Military History.

Still, in September 1944 the situation favored the Allies, who advanced steadily, if slowly, in the face of hasty counterattacks conducted by badly understrength Wehrmacht units. By late September, however, the logistic situation grew critical, dispersal of forces made Allied attacks ineffectual, and the enemy began to recover. As the pace of the Allied advance slowed, the Wehrmacht prepared a powerful defense along the Siegfried Line, known to the Germans as the “West Wall.” This was the last line of defense standing between the Allies and the German frontier.

With fresh troops bolstering the defense of Aachen and a VII Corps attack south of the city stalled by a tenacious defense, Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges, commander of the First US Army, ordered a pause on September 22, halting offensive operations through the end of the month. The pause would give him time to reorganize his troops and develop a plan to resume the offensive in early October. To help in this effort, Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, commander of the 12th Army Group, ordered Lieutenant General William H. Simpson’s Ninth US Army to move from Brittany, France, into the line, taking up a position between the Third US Army to the south and First Army to the north. This shortened the First Army front, enabling Hodges to concentrate forces for a renewed offensive into the Aachen Gap, a stretch of armor-friendly terrain just north of Aachen, Germany.

Major General Raymond S. McLain, XIX Corps Commander. Photo: ibiblio.org

Hodges ordered Major General Raymond S. McLain, commander of XIX Corps, to prepare for the offensive. The 30th Infantry Division, commanded by Major General Leland Hobbs, would spearhead the attack along a 14-mile front stretching from Geilenkirchen in the north to Aachen in the south. Hobbs’s troops would drive east to the Roer River and then south to Aachen, reducing the Siegfried Line, clearing the area of German troops, and linking up with the 1st Infantry Division on the northern edge of Aachen. The 117th and 119th Infantry Regiments would lead the attack, fighting abreast, with the 120th in reserve. The 29th Infantry Division, recently returned to XIX Corps command after the liberation of Brest, would secure the corps’ left flank during the offensive.

Major General Leland S. Hobbs, commander of the 30th Infantry Division. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

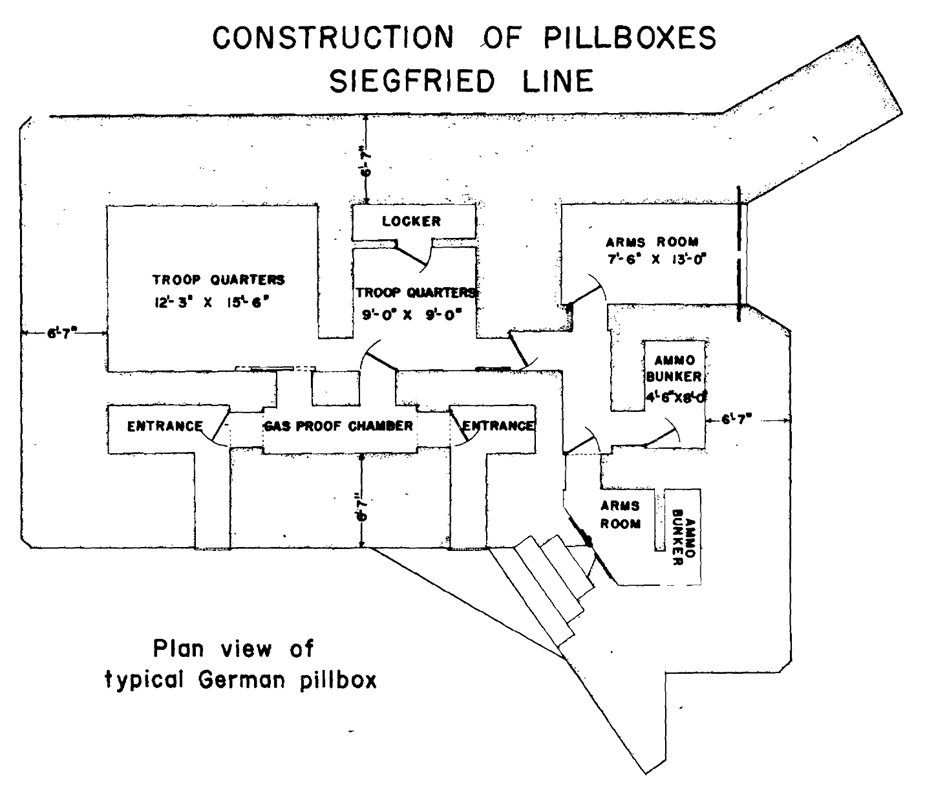

The Siegfried Line was a formidable series of obstacles intended to bolster the defense along the German border. Defending forces, protected by steel-reinforced concrete pillboxes, trenches, and other fortifications, overwatched these obstacles. Never intended to stop an attacker on their own, the Siegfried Line increased the defender’s survivability while slowing down attacking troops, increasing their exposure to machine gun, artillery, and antitank gun fire. Once they assessed that the attacker was weakened sufficiently, the Germans would inevitably counterattack.

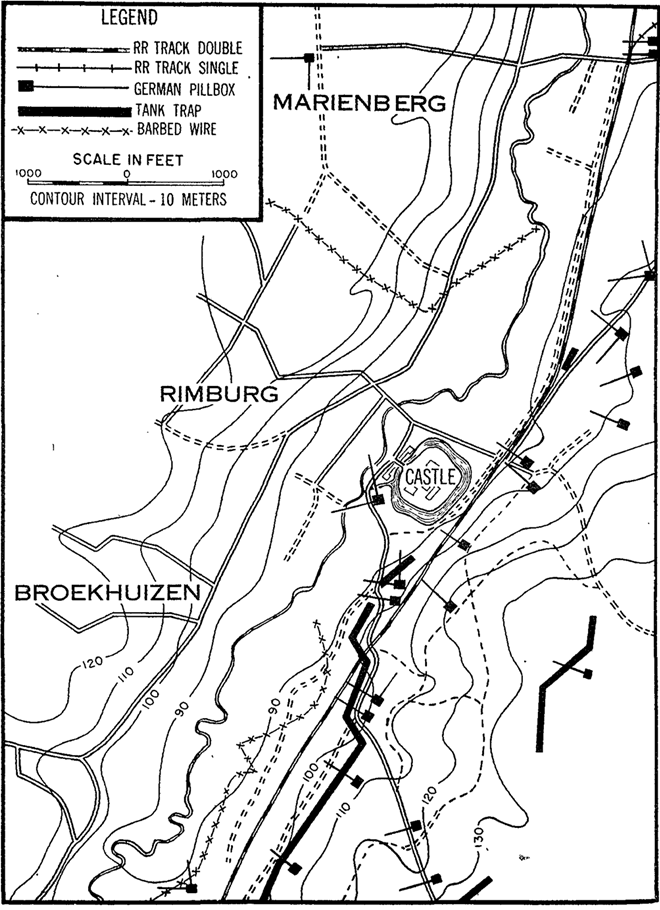

30th Infantry Division zone of attack. Leland Hobbs, “Breaching the Siegfried Line,” Military Review, Vol. 26, No. 3, June 1946

The Siegfried Line supplemented the natural defensive characteristics of the terrain. In the 30th Infantry Division sector, which consisted of relatively open terrain, the Wurm River presented the first natural obstacle. The Wurm was 30 feet across, with steep, muddy banks on either side, making it impassible to armor without combat engineer bridging support. Only a small portion of the line just north of Aachen lacked this water obstacle, so here the defensive belt included the only dragon’s teeth in the XIX Corps sector. Just to the east, a parallel railroad line ran through the Wurm River valley, further complicating the terrain. Finally, the center of the 30th Division sector featured a castle with a moat, situated in dense forest on hilly terrain. The Siegfried Line, three kilometers thick and dense with pillboxes, backed up these natural defenses.

Dragon’s teeth, one of the most recognizable obstacles used in the Siegfried Line, near Wissembourg, France. Courtesy The National WWII Museum

The Germans built the Siegfried Line from 1939–40, so they designed the pillboxes around the most prevalent weapons of that time: the machine gun and the underpowered 37 mm antitank gun. This meant the pillboxes were too small to house more modern weapons like the feared 88 mm antitank gun. Still, they presented a serious challenge to the enemy, supplementing the trenches, foxholes, minefields, and antitank obstacles making up the defense.

To prepare, Hobbs rotated his troops out of the line in the period preceding the attack so that they could conduct training. Planners built a large terrain model—a detailed representation of the terrain and the obstacle belt—with each pillbox in its confirmed location. Soldiers prepared diligently, learning how to spot concealed or disguised pillboxes, and practicing detailed procedures for reducing them. This training was essential, enabling the GIs to react instinctively to the demands of the mission.

Plan view of a typical Siegfried Line pillbox. XIX Corps, US Army, “Breaching the Siegfried Line,” 12 January 1945, Combined Arms Research Library, Call Number N-7623.

Both field artillery preparatory fires and an aerial bombardment preceded the attack. Beginning on September 26, the 258th Field Artillery Battalion’s M12 155 mm self-propelled guns pummeled the German fortifications daily. Unfortunately, post-battle damage assessment revealed that only the 155 mm or 8-inch howitzer could penetrate the reinforced concrete pillboxes, and they could do so only after scoring three to five direct hits. Artillery proved effective mostly in forcing German defenders to remain in their pillboxes, or in causing the surrender of the demoralized occupants of a pillbox who experienced a direct hit. Therefore, after nearly a week of artillery bombardment, most of the fortifications remained intact.

Camouflaged German pillbox. XIX Corps, US Army, “Breaching the Siegfried Line,” 12 January 1945, Combined Arms Research Library, Call Number N-7623.

On the morning of the attack, October 2, the focus of the artillery shifted to counter-antiaircraft (AA) fire in support of the aerial bombardment. The guns of both the XIX and VII Corps artillery targeted AA positions, their precise locations confirmed by aerial reconnaissance. These fire missions were highly effective at suppressing or destroying the AA batteries, resulting in zero losses of Allied planes. The results of the aerial bombardment were less impressive, however. Most of the medium bombers approached the target area from the west, rather than from the southwest, as intended. This created confusion among the bombardiers, most of whom did not release their loads. The fighter bombers dropped napalm on the pillboxes, aided by the placement of red smoke near their targets, but this, too, had limited effect. It would be up to the infantry and their supporting arms to reduce the fortifications in close combat.

XIX Corps Breaks Through the West Wall, 2–7 October 1944. US Army Center of Military History.

The infantry assault began at 1100, with the 117th Infantry in the north and the 119th in the south. The GIs of the 117th rushed down the hill to the Wurm River under a hail of German small arms, mortar, and artillery fire. Engineers threw specially constructed footbridges across the river in minutes, allowing the infantry to sustain its momentum, minimizing the troops’ exposure to fire. Supported by self-propelled 155 mm artillery, the infantry began the work of reducing pillboxes. By the end of the day, the 117th reached Palenberg, its objective for the day, having reduced 11 pillboxes, without armor support, at the cost of 227 casualties.

The 30th Infantry Division intelligence officer reported after the battle that the pillboxes were:

"in clusters, all inter-supporting and sited to cover each other by fire. But due to the limited traverse of their fields of fire, there seemed to always be one at least in a group, which, if reduced, permitted our men to start a circuit of the remaining pillboxes, using approaches to each succeeding one that could not be covered by fire of the remaining ones. The problem of course, was to discover the key pillbox to each cluster.[1]"

For the 117th, attacking fortifications in the open, this was a relatively easy task. The 119th faced a tougher challenge, attacking up a steep slope into dense forest that was too damp to ignite with napalm. The trees made detection of pillboxes and enemy movement challenging, while making American artillery fire ineffective against the pillboxes. This forced the infantry to attempt a frontal assault into the forest, but German artillery intensified, with aerial bursts exploding in the treetops, creating deadly wooden splinters and making it impossible to install a bridge over the Wurm. The Rimburg Castle, surrounded by minefields and a moat and supported by observation posts on the high ground, further complicated the situation

Rimburg Castle, moat visible in the foreground. XIX Corps, US Army, “Breaching the Siegfried Line,” 12 January 1945, Combined Arms Research Library, Call Number N-7623.

As the XIX Corps reported in its after-action report, “The mission of the 119th in breaching the Siegfried Line soon boiled down to the job of effecting a penetration of the woods, and then cleaning out the enemy . . . after close-in fighting with opposing lines rarely getting further apart than twenty-five to fifty yards.”[2] This delayed the 119th Infantry’s advance while greatly limiting the effectiveness of their artillery and armor support.

The 2nd Armored Division crossed the Wurm and joined the fight in the northern part of the corps sector on the morning of October 3. Predictably, the relatively open terrain enabled rapid movement of the tanks, which proved mostly impervious even to the most intense artillery fire. By the end of the day, armored elements pushed through and cleared the town of Ubach. German counterattacks began the next day, but despite experiencing the most intense artillery bombardments of the war up to that point, the infantry with their supporting armor beat back these attacks. Meanwhile, the 119th Infantry cleared the Rimburg Castle by the evening of October 3, pushing south of the castle to the railroad on the 4th.

With the 117th Infantry’s zone mostly cleared, on October 5 the focus of the attack shifted to the southeast. The 119th Infantry, reinforced by the 3rd Battalion, 120th Infantry, gradually pushed south through the woods. At 1330, Combat Command A of the 2nd Armored Division crossed the Wurm and passed through the 117th, rapidly extending the American lines to the east. The Germans launched their most powerful counterattacks on the morning of October 6, recapturing four pillboxes and forcing the 2nd Battalion, 119th Infantry, to retreat 800 yards with significant casualties. By nightfall, however, the infantry regained their initial positions as German resistance crumbled, although fighting continued until October 16, when the 30th Infantry Division made contact with the 1st Infantry Division just northeast of Aachen.

As noted in its after-action report, by October 16 the XIX Corps had destroyed the enemy positions of the Siegfried Line in their 14-mile-wide zone of attack, penetrating to a depth of six miles. Success was costly, however, especially in the south, where the 119th and 120th Infantry suffered about twice as many casualties as the 117th. Post-battle analysis revealed the difficulty of clearing the densely wooded terrain in the southern part of the corps sector. This should have informed planning for future operations, but it did not stop the Americans from attacking into the strongest portions of the Siegfried Line in the coming weeks.

Historians have argued that the Allies should have remained in the defense south of Aachen and mounted an offensive through the Aachen Gap. This would have sidestepped the Hürtgen Forest—with terrain much like that faced by the 119th and 120th Infantry—avoiding one of America’s longest and most costly battles of the war. The logic of Eisenhower’s broad front strategy, however, required Allied attacks to continue all along the line. Though intended to destroy the German army west of the Rhine River, this attritional strategy also increased Allied casualties and possibly delayed victory in the European theater for months.

ADDITIONAL READING:

Robert W. Baumer, Old Hickory: The 30th Division, the Top-Rated American Infantry Division in Europe in World War II, Lanham, MD: Stackpole, 2017.

XIX Corps, US Army, “Breaching the Siegfried Line,” 12 January 1945, Combined Arms Research Library, Call Number N-7623

CONTRIBUTOR

Dr. Mark T. Calhoun

Dr. Mark T. Calhoun is the Military Historian at the Jenny Craig Institute for the Study of War and Democracy.